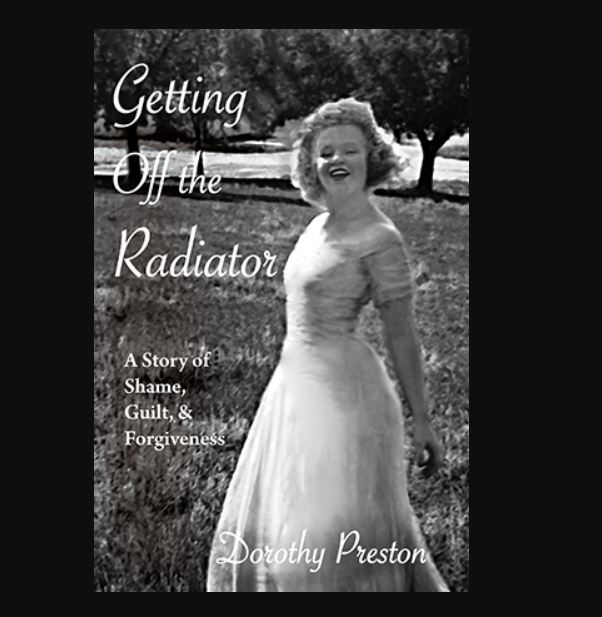

Dorothy Preston’s autobiography, Getting Off the Radiator, is a striking example of how hardship can build resilience. Her story, which is set in a twenty-eight-room mansion that should have suggested privilege but instead concealed dysfunction, poverty, and despair, is remarkably successful in showing how appearances can be deceiving. A broken family fought to survive in that dilapidated home, which was inhabited by roaches, drifters, addicts, and even criminals. Preston, the youngest of seven siblings, was trapped in a bizarre and extremely painful childhood.

The symbolism of the book’s title, “Getting Off the Radiator,” seems especially avant-garde. It suggests a moment of decision where bravery is needed to survive by conjuring the act of removing oneself from what burns and confines. Preston shows that the first step to healing is to leave the burn behind, whether it be guilt, shame, or rage. This metaphor is instantly understood by readers as both literal and metaphorical, and it powerfully grounds the story.

| Category | Details |

|---|---|

| Full Name | Dorothy Preston |

| Profession | Author, Editor, Publishing Professional |

| Notable Work | Getting Off the Radiator: A Story of Shame, Guilt, and Forgiveness |

| Publication Year | 2021, Shanti Arts Publishing |

| Genre | Memoir, Autobiography |

| Education | Degree in Communications/Media |

| Career Background | Over 20 years in publishing (Prentice Hall/Simon & Schuster, Houghton Mifflin, Little Brown) |

| Residence | Massachusetts, USA |

| Interests | Hiking, cycling, skiing, running, writing |

Growing up with a mother who was battling alcoholism and poverty after her father abandoned them, Preston witnessed chaos permeate every aspect of day-to-day existence. Shame and rage took center stage in this twisted fairy tale set in the mansion. Her siblings’ propensity for destructive behaviors was a reflection of remarkably common coping mechanisms observed in many bereaved families. Preston’s honest account of her own mistakes makes it particularly compelling as testimony because she doesn’t minimize or hide the truth of those decisions.

The book’s focus on forgiveness is what turns it from a tragedy to a victory. Preston sets an example that is especially helpful for readers coping with their own burdens by facing her past and making the decision to forgive—not just her parents and siblings, but also herself. Her insistence on forgiveness as liberation seems incredibly effective at slicing through resentment at a time when blame is a common topic of public discourse. It serves as a reminder that choosing not to allow scars to shape our future is a better way to achieve peace than trying to erase them.

The memoir’s structure and style are remarkably effective, having been honed by two decades of publishing. Although she was editorially prepared by her work at Prentice Hall, Simon & Schuster, and Houghton Mifflin, her debut is notable for its vulnerability. Her work is in line with other unvarnished memoirs such as Tara Westover’s Educated and Jeannette Walls’ The Glass Castle because of this vulnerability. A common theme among all three is turning chaotic upbringings into inspirational stories.

Preston’s portrayal feels especially novel because she frames her journey as a component of a larger human pattern rather than as a singular victory. Her story will resonate with many readers as it reflects their own silent struggles. The book is extremely versatile because of this resonance; it is simultaneously literature, therapy, confession, and guidance. Its authenticity is further enhanced by the addition of family photos, which guarantee the reader sees more than just words but also real shards of lived history.

It is noteworthy that Preston’s memoir has wider social significance. Her story serves as a remarkably powerful contribution to cultural discourse at a time when conversations about trauma, therapy, and generational cycles of pain are finally making their way into the public eye. She makes others feel less alone by exposing the dysfunction in her own family. Memoirs have emerged as a particularly creative genre for igniting change in recent years, and Preston’s work blends in perfectly with this expanding trend.

Her present life, which includes cycling, skiing, hiking through the hills of Massachusetts, and establishing a new life in Maine, offers a hopeful contrast to her challenging past. It proves that happiness and scars can coexist and that a peaceful future is not predicated on dysfunction in the past. This metamorphosis is similar to the reinvention arcs of individuals such as Drew Barrymore, who restored stability after a chaotic upbringing, or Oprah Winfrey, who transformed childhood trauma into worldwide influence. Preston’s tale fits into that tradition of reimagining.

Her candor is both shockingly uplifting and painfully raw for readers. She acknowledges her mistakes and has the guts to move on without providing any justifications. Many memoirs run the risk of either rushing toward redemption or wallowing in pain, but Preston strikes a strikingly clear balance. She demonstrates that life is a combination of both tragedy and redemption. Because of this subtlety, the book is a very effective empathy teaching tool.

In the end, Getting Off the Radiator is more than just a survival narrative. It is a call to consider how we all deal with guilt and shame and whether we are prepared to forgive in order to move on. Dorothy Preston provides a unique viewpoint on human resilience by fusing universal themes with personal anecdotes. Her story, which is intensely personal but remarkably similar to many silent struggles, serves as a collective testament: scars can define us, but only if we allow them to do so.